Paul McCartney’s Neglected Masterpiece

by KYLE SMITH

April 13, 2017

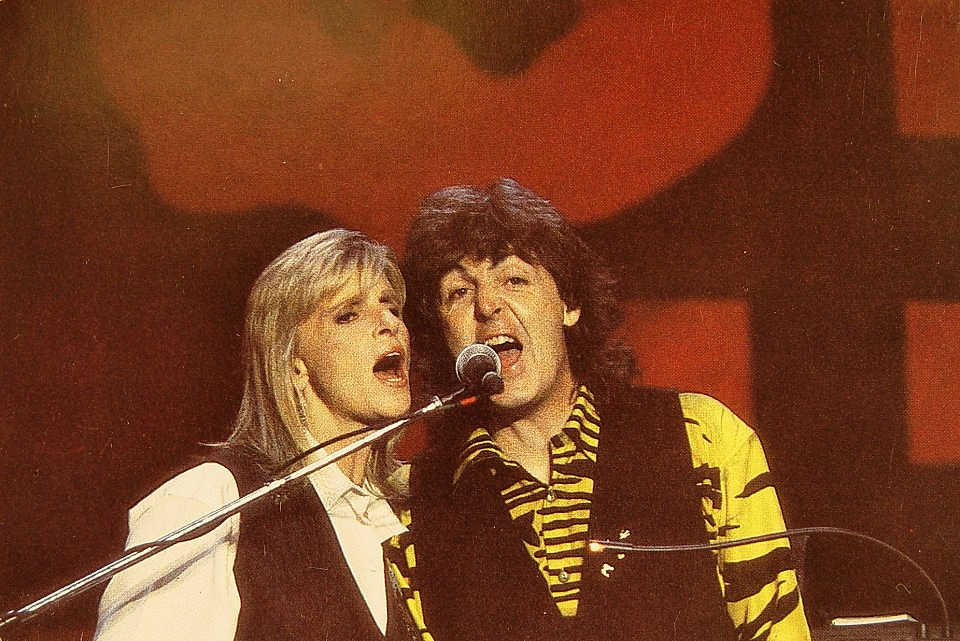

McCartney performs at the Hollywood Bowl in 2010 (Reuters photo: Mario Anzuoni)

Flowers in the Dirt, newly rereleased, is Paul at his mature best.

Unlike John Lennon, the chronic oversharer avant la lettre, Paul McCartney has always been guarded about his interior life, rarely using his songs to deliver the gossip about what it’s like being Paul McCartney. For McCartney, the entertainer’s imperative is to entertain, not broadcast his angst. Moreover, he seems to find it necessary to guard, to fence off, his actual self, forever presenting himself to the world as relentlessly afflicted by goofy joy. In the immortal phraseology of a now-defunct music magazine, he is Fab Macca Wacky Thumbs Aloft.

Yet on his 1989 album Flowers in the Dirt, McCartney showed, in the track “Don’t Be Careless Love,” a tormented side. The speaker, noting “the midnight lamp” burning down, resolves to stay up until his love returns home. He continues:

In my dream you’re running nowhere

Every step you’ve taken turns to glue

Walking down a spiral staircase

Falling through, falling through.

Later the singer worries about his companion being “chopped into little pieces / by some thugs.” It might be the most haunted, introspective song McCartney has ever written. For the man with everything, only one thing really mattered: Linda, his wife from 1969 until her death in 1998. McCartney used to say that all the love songs he wrote during their relationship were about her, and in this fragile yet sweeping spiritual he told us everything about what she meant to him.

Fine as it is, though, “Don’t Be Careless Love” isn’t even one of the five best songs on the masterly Flowers in the Dirt, one of the handful of great albums McCartney did after the 1970s (along with 1982’s Tug of War, 1997’s Flaming Pie, and 2005’s Chaos and Creation in the Backyard). Flowers has just been rereleased in various formats, including a sumptuous boxed set containing the original, remastered album plus unreleased demos (some of them collaborations with Elvis Costello), gorgeous artwork, and charming facsimiles of handwritten letters to McCartney, including one from his new songwriting partner. “Greetings from dirty old Dublin,” Costello wrote in an undated note reprinted on pink paper. “We are in our last couple weeks here and the place is going upside down with U2 fever.”

It’s a cliché to say that Lennon gave McCartney the hard backbone without which his cottony songs would have collapsed, but the value to Flowers of the contributions by the ironical, sentiment-averse Costello and the hard-rock Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour is unmistakable. Costello co-wrote the album’s magnificent centerpiece, “That Day Is Done,” a slow-burning gospel-infused anthem of confessed “shame” and “sorrow” sung, we come to understand with a shiver, from the grave:

She sprinkles flowers in the dirt

That’s when a thrill becomes a hurt

I know I’ll never see her face

She walks away from my resting place.

“That Day Is Done,” a thing of power and majesty, is more mature and reflective than any of Lennon’s supposedly serious efforts. But it is matched in its force by an entrancing hard-edged rock number, “We Got Married,” to which Gilmour contributes one of his very best guitar solos, a choppy, furious interlude that turns this love song into a kind of argument with itself. Great love stories almost invariably end in marriage, but what, McCartney asks, happens after that? That’s where the work begins, where the real devotion shows.

A half-inch analogue stereo mixtape from the “Flowers In the Dirt” recording sessions. (MPL Communications Ltd./Copyright 1987 MPL Communications Ltd. )

In McCartney’s case, marriage directly preceded the breakup of the Beatles and a bout with depression in the early 1970s, when the four-man fraternity dissolved in an acid bath of litigation, and he felt he had lost his purpose. “Working hard / for the dream / Scoring goals for the other team” appears to be a reference to those times, and as he muses about raising children, he adds, “Place your bets / No regrets / We got married.” Juxtaposing such uncharacteristically equivocal thoughts with those fierce, almost bitter, Gilmour guitar licks, McCartney gets at just how much grit and determination it requires to keep any marriage going (not to mention the crystalline vulnerability of celebrity marriage). Coming at the same subject from an oblique angle, “Distractions” not only contains one of the most gorgeous melodies McCartney ever wrote, but it elegantly maps out the mindscape of middle age, when life seems clogged and rerouted by a thousand frustrating irrelevancies, each of them undermining one’s hopes to accomplish anything much. As McCartney’s late friend once put it, life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.

The singles on Flowers, none of them big hits, weren’t well aligned with the musical tastes of 1989, but they’re winners, too, showing off both McCartney’s bright, bouncy “Hello Goodbye” side and his placid, just-strumming-under-a-tree tenderness. “This One” (a modest hit on the U.K. singles chart) unfolds from a Moody Blues–style intro into a bonanza of happy sounds reminiscent of peak Beatles. “Put It There,” the title of which drew on a favorite phrase of Paul’s ineffably affable father, Jim, finds McCartney in “Blackbird” mode, building on a gently appealing acoustic-guitar line. “Figure of Eight,” an expertly crafted rocker with a hoarse lead vocal, has a touch of mid-’70s Wings. Even the Costello-co-written “My Brave Face,” which was the first single chosen for release despite (or maybe because of) its being one of the few slightly generic-sounding tracks, grows infectious after a few listens, and its funny lyrics, about a bewildered middle-aged man who can barely operate a microwave after his woman leaves him, are alive with the self-deprecating mordancy Costello borrowed from Lennon.

Prior to Flowers, the last album of original material McCartney had released, 1986’s Press to Play, was so pitiful that even we stalwart Macca defenders found ourselves looking at our shoes and mumbling, “It’s not so bad as all that.” But long after his detractors simply wrote him off, McCartney was still pushing himself, still proving capable of making exceptional pop music. It’s easy to deride his post-Beatles work, or his post-Wings work, as rubbish, but only if you don’t actually listen to the best of it.

— Kyle Smith is National Review’s critic-at-large.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario